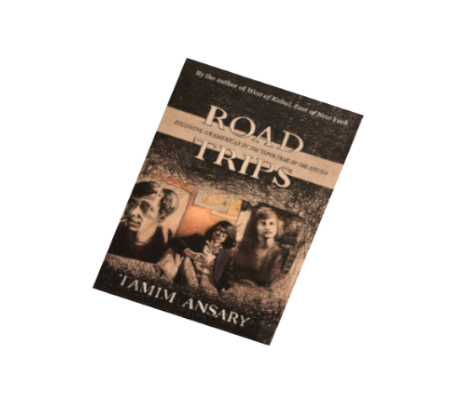

Tamim Ansary

Recently, someone asked me what books have had a big impact on my life. I went blank for a moment, even though, until I was in my 20’s, I inhaled books the way speed addicts snort coke. Then a novel popped into my head: Death on the Installment Plan, by Louis Ferdinand Celine. I read it the year I moved to San Francisco and started working for an outfit called The Asia Foundation, my first real job.

The novel is about a young boy from a very poor family in Paris whose parents are desperately trying to equip him for life by placing him in some situation that can grow into a career. Ah, but he’s a scamp, oblivious to his parents’ desperation. He just wants to run off and play, and what can you expect? He’s a little kid, that’s how little kids are: it’s the Pinocchio syndrome. And so we follow this kid through a series of circumstances his parents put him in, each one more hectic and awful than the last.

All of these episodes follow a pattern, but the one I remember best is when the little boy’s parents apprentice him to a man who publishes a magazine about inventions. It’s a bustling enterprise with a wide readership, because it’s the early 1900s, a boom-time for technology, and lots of people are fascinated by inventions. When our hero is given a place there as an errand boy, his parents feel like, phew! Finally, they’ve found a niche for him! Here, their little boy can learn marketable skills and become employable. What he’s got his foot on is the first rung of a ladder, and all he has to do now is climb that ladder, rung by rung, climb and climb: eventually he’ll be in a position to earn a living as a respectable member of society.

But a crucial portion of the magazine’s money, it turns out, comes from a contest it runs periodically for inventors. People send in blueprints of gizmos and gadgets they’ve invented, and the magazine picks a winner. They publish an article about this winner and give him a prize. The magazine has some status, so winning the contest confers prestige on the winner and gives him a leg up on securing a patent and getting investors interested.

But it does cost a little money to enter the contest. Not much, but a little. The magazine gives out only one cash prize, a sizable one, but the magazine rakes in tons of money, because most of the would-be inventors competing for the prize are kooks, basically, and there are tens of thousands of such kooks in France in this era. Eventually the kooks realize that 99.9% of them have no chance of winning the prize, and were never intended to, and they begin to picket the magazine. The pickets turns into protests, and soon mobs of kooks are closing in on the offices of the magazine. The publisher and the boy escape with their lives, and the boy goes back to being just another penniless urchin with desperate parents.

Later in the book, the parents get their son, now a young man, a job with a private school in England. He’ll be earning a salary, learning administrative skills, and picking up English, which will land him translation jobs in the trading sector when he gets back to France. What his parents don’t know, however, is that the school is coming unraveled. Its buildings need repairs, it owes money, some of the teachers have left. The school officials can’t let any hint of their troubles leak out to the parents or to anyone else really, because the school’s survival depends on the tuition money flowing in. That money will keep coming as long as the parents think the school is still running and their kids are actually getting an education. So the school officials keep publishing ads, keep sending out report cards, keep giving the parents and public a rosy picture of the learning environment—while in actuality, they’ve lost their buildings and property, they’re living in tents in the parks, and the remaining faculty and students have devolved into a horde of petty criminals foraging through the neighborhoods like feral creatures.

This book is embedded in my memory because as I was reading it, I saw that Celine was illustrating a profound truth about social reality—its existence depends entirely on belief. As long as everyone believes a social institution exists, it does exist. All the enterprises Celine dramatizes operate on the belief of others that they are what they say they are, and as long as the belief is solidly there, the enterprises do just fine, they can keep going. As soon as the belief starts to fade, the enterprise begins dissolving into an illusion.

As I mentioned, I was working for The Asia Foundation at the time: it was my first “real” job, by which I mean it was the first job I had that was appropriate for a person of my supposed credentials and social background. I was born into a family that enjoyed respect in Afghanistan on account of its intellectual traditions. I came to America where I was a curiosity from an exotic place that nobody had ever heard of at the time. Somehow this was a plus on a college applications. This distinction was the one real asset I brought to the table, but with this chip, I was able to get into some well-respected schools: first Carleton College, and then Reed, from which I graduated with a B.A. in literature. Presumably, this gave me the tools to make something of myself; but I didn’t know how to make any actual thing of myself. For the first six years after graduating college, I had lots of jobs but none that required the college degree I had earned. I was an assembly worker in a furniture factory, then a warehouse clerk, then a postal worker, then a waiter.

The only thing I really knew how to do was read books for edification and enjoyment; so the only thing I could think to be was a writer. The works I liked to read were short stories and novels, both literary and commercial. So when I sat down to do what writers do, I wrote short stories and novels. I sent the former out to magazines like the New Yorker and the Atlantic Monthly; then to literary magazine such as the Paris Review and Ploughshares; then to eccentric little literary magazines such as Jabberwacky and Briccolage—oh, you haven’t heard of those? Well, that’s my point. Even those magazines, which paid only in contributor copies, usually sent back form-letter rejection slips. With those rejection slips, they sometimes included subscription forms.

Sometimes, these magazines which paid zilch also charged money for reading your work. If you wanted to submit something for consideration, you were welcome to do so: you just needed to include a check for ten dollars and a stamped, self-addressed return envelope. Sometimes, some of these magazines ran contests. The winner got a cash prize and a credit to tout when they went to publishers with their novel.

Such was the world I saw around me the year I was reading Death on the Installment plan and working at the Asia Foundation. Celine was describing both the Asia Foundation where I was working and the world of literary magazines that I was trying to push my way into.

And what was The Asia Foundation? It wasn’t something that existed in objective reality as a material fact. It was an idea that existed in the social landscape only because many people could see it. We told the world we were an entity that sent people to poor underdeveloped parts of Asia, places like Afghanistan; there, our people looked for interesting projects that needed just a little money to get over some hump; and we gave them that little bit of money. Wherever we did this, seeds sprouted and good things grew. By making this case, we convinced people who had money to give us some of that money so we could do this wonderful thing that we did.

Were we really watering seeds that grew into lush gardens? Well, you know, nothing’s perfect. As long as people believed we were doing it, the money kept coming in. We all got salaries. We paid our rent. We bought groceries, we went out to eat. We took vacations. Belief was the fire we had to keep feeding, in order to keep our enterprise going.

Let me interrupt myself to note: The Asia Foundation actually was busy trying to do what it said, and it did have some good projects, and it might have been doing them too, for all I know. But what did I know: I was in San Francisco, the projects were in Asia. The point I want to press is this: whether or not we were successfully doing what we said, we would have said we were, because our existence depended on saying it and on people believing it to be true.

As soon as I saw this about the Asia Foundation, I could see it in everything around me: because the landscape I lived in most significantly was not the physical world but social reality. Social reality felt as solid as the material facts of the physical universe I could see with my eyes and touch with my fingers. Yet its fundamental substance was nothing but a fabric of belief shared among a crowd of people. Clubs and countries and corporations, fellowships and foundations and communities—they all felt like they existed in the same way as rocks and rivers and clouds, but actually, they existed only as incarnations of belief. Mountains are something we see because they are there. Countries by contrast are there because we see them. This was the idea that emerged for me out of Celine’s novel Death on the Installment Plan, back in 1978, when I was working at the Asia Foundation, laboring to be a writer who would, I assumed, not be appreciated until long after he was dead.