What’s your earliest memory?

Someone posed that question one day, when a bunch of us were sitting around chatting idly about life. I didn’t have to think about it.

Or at least—thinking had nothing to do with what abruptly happened. An earliest-memory flashed up inside me immediately, bright with color, rich with detail. I don’t know if it was actually my “earliest” memory, but it was certainly a very early one. I must have been about three.

Since then, I’ve lost access to the memory itself. I cannot now see all that color, all those details. What I have left, now, of that “earliest memory” is just data: just information. But when I recount the information, I experience brief glimmering glimpses of a remembered life. Each flash sets off another flash which sets off another flash, which sets off another and another, because that’s how memory works: link to link to link.

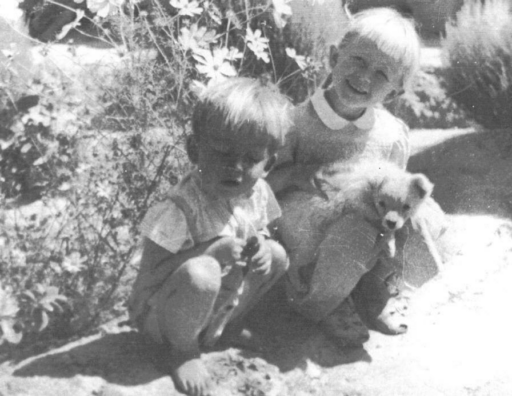

I can say with confidence now, for example, that we lived in Kabul when this remembered episode happened. My father taught something, I never knew what, at the University. My mother taught English at Malalai, the first girls’ school in Afghanistan. My parents also had a classical Western music program on Radio Kabul, which aired once a week. They did the show live, which means they went to the studio on those nights, and played records on the radio. We at home—my sister Rebecca and I—listened to the radio on those nights. The program intro was the William Tell Overture. I can still hum that tune on command.

My mother was ferociously devoted to classical Western music, and my father seemed equally devoted, although he had other interests as well. He listened, frowning, to the news in the evenings, which was delivered in both Farsi and Pushto on Kabul Radio. After the news he listened to the local musicians they broadcast: Ustad Sarahang is the one I remember: a classical master.

Kabul Radio played popular Indian music as well. But we didn’t have to listen to Kabul Radio to get Indian music. We had a record player of our own at home—a record player! An amazing new piece of technology at the time, at least in Afghanistan. And we had popular Indian and Arabic records to play on our record player: there was Lata Mangashkar, the foremost pop singer of India at the time. She sold way more records than Elvis Presley ever did, if I’m not mistaken. And later we had Ferouz records: she was the leading female pop singer of the Arab world. The record were ‘78s: about the size of dinner plates and made of hard plastic. The smaller “45s” that played a single song on each side came later; and the thin, flexible discs known as 33s, later still.

We lived in a yard surrounded by a wall, and we kids never wandered out of that compound by ourselves. But we traveled sometimes, with family, to other compounds. I have vague impressionistic memories of weddings, and of being at my grandmother Koko’s house. I have memories of her and others, telling stories around the sandali, a big low table set in the middle of the room and covered with a heavy blanket. Under the table was a pan with hot coals. We kids and adult storytellers sat around the table, under the blanket, huddled together warm and cozy, listening with rapt attention to stories filled with magic and fabulist imagery.

I have a couple of sharp memories of riding on the back of a bike about that time, with my cousin Khalil operating the pedals. He was probably 10 years older than me, an adult to my eyes: I remember him taking me somewhere beyond the traffic circle that interrupted Deh Mazang Highway, the road nearest to our house, a ten-minute ride across an empty field–unless a band of nomads was camped there. They came every so often and when they did, you had to skirt their encampment. You didn’t want to get close to that ominous clump of black tents. Big mastiffs with enormous jaws patrolled the environs of the nomad camp.

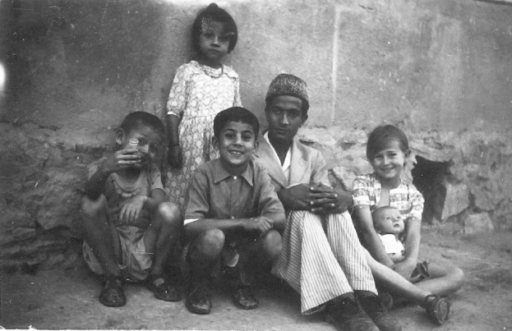

My best friend at that time was Suleiman Shah, a boy who lived in our yard. I was told his family were kinar-nisheens of ours. Kinar-nisheen means “the ones in the corner.” They were a poor family living in the corner of our life. We lived at the edge of the city, and it wasn’t good to be alone out there, because bandits sometimes came over the walls at night. Daddy, as we called our father, felt that we would be safer with more people in the yard, so he found this other family and gave them rooms separate from ours but within the protection of our same walls. They didn’t pay rent, they didn’t work for us, they weren’t our servants. They had their own life separate from ours. The mother was the homemaker for that family. She had a baby, and a boy my age, and she cooked and cleaned and shopped for her family. The man of that family went out and did some job somewhere.

They didn’t work for us, but there was never any doubt that they were on a social level below ours. I don’t remember some revelatory moment when I realized all this, and after I realized it, I had no judgment of it. I was busy trying to bring the world into focus. Where was I? Who was I? What was this place? What was I doing here? What was I supposed to be doing? Who were these people I was living with? What was going on in this place? As the picture came into focus, a life that was mine came into focus. As this life came into focus, I came into focus, for myself. The person living this life? That person was me. Who was I? The person living this life. Now I understood. Sort of.

Me and the little boy of this other family were buddies. He was a street-wise kid. I was very fragile, very much in danger of being broken. I knew this to be the case because my mother let me know. I should never leave the yard alone, I should be very cautious around strangers. Everyone I met might mean me harm. My buddy’s family wasn’t precious about him. If he wanted to go out, he could go out. He didn’t have to ask anyone, he just went. No one tracked him or set schedules for him. To me, therefore, he was the guy who knew what was what out there in the wilds. From him I could learn.

We used to hang out in the kinar-awb and talk naughty. The kinar-awb was the outhouse. It’s where people went to poop, so it smelled like shit in there, but I didn’t notice the smell much, it was just a normal part of where I lived. And there I sat with Suleiman Shah, on a little built-in mud bench, and he told me about his adventures in the world outside the compound walls. He told me he regularly sneaked into all the other compounds in the neighborhood. In many of them, he told me, he had girlfriends and he fucked them regularly.

We were, let me emphasize, four or five years old at this point.

Sometimes, he told me, he refused to fuck one of his girlfriends and this made her very distraught, he said, very sad. I listened goggle-eyed to these reports. What a world it was out there! How I wished my mother would let me go out there sometime. I had no idea what fucking was, but it sounded like kite flying, from the way Suleiman Shah talked . On Fridays, sometimes, dozens of boys flocked to that big empty field outside our compound and flew kites. I wasn’t allowed out there, and I didn’t know how to make or fly a kite, but I longed to try it. If fucking was anything like kite-flying, I wanted to try that too, if I ever got a chance. I knew I never would, of course. A guy like me? Not a chance. But a boy can dream.

These are some of the memories I can get to, link by link, from that vivid glimpse that flared inside me when someone posed the question “What’s your earliest memory?” The memory itself, however, I can no longer access. My access to the vivid moment itself has washed away like a bridge in some storm. The information remains, but not the lived experience of three-year-old Tamim, not the aroma of hot chocolate on that morning, nor the rainbow-colored bubbles in the chocolate, nor the emotion that swamped that boy when the meaning of the bubbles hit him. Today, I remember that moment only as the image that flashed in me when the question was asked: only as a fleeting fragment of a larger, later memory.

So today, I can only access the rainbow-colored bubbles in that hot chocolate through the memory of an afternoon in 1973, in a house in Portland, Oregon, on the corner of 27th and Main Street, when twenty-five year old Tamim was telling the story of his earliest memory, to Margo, who lived in that house, and to Beth Glazer, whom I met there. Margo I still know, but Beth I never saw again after I left Portland.

But even as I write these words I realize that, no: that actual memory is gone too, because I wrote about the day the question was posed when I was fifty years old and writing a book called Road Trips, a memoir about the Portland years. So today, when I bring up the earliest-memory-story, what I’m actually experiencing is being fifty years old and working on Road Trips.

And someday, I realize, all of this will exist only as a memory of 76-year-old Tamim, sitting in his basement office, late one November morning, in San Francisco, working on a post for this website.